En kiosque

Le Magazine des Livres n°20, Novembre/Décembre 2009

Sommaire

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

| Fascismo, Nazionalsocialismo, gli Arabi e l’Islam

| |

|

|

| |

| Giovanna Canzano ha incontrato per Rinascita lo scrittore e storico Stefano Fabei Nei primi otto anni di potere Mussolini non portò avanti un’autonoma politica araba per diverse ragioni: la politica estera italiana aveva come punto di riferimento quella inglese e dall’andamento dei rapporti con la Gran Bretagna dipendeva l’atteggiamento di Roma verso gli arabi; inoltre gli impulsi a una politica estera rivoluzionaria, verso questa parte del mondo, sostenuta dai fascisti più dinamici, erano soffocati dall’influenza esercitata sul regime da nazionalisti e cattolici conservatori. |

00:10 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : monde arabe, islam, italie, allemagne, années 30, années 40, deuxième guerre mondiale, seconde guerre mondiale, méditerranée |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Roberto ALFATTI APPETITI:

Roberto ALFATTI APPETITI:

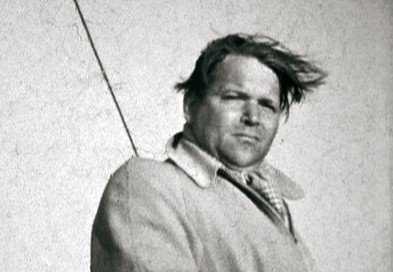

Giuseppe Berto, écrivain proscrit et oublié

Malgré une biographie, remarquable de précision, publiée en 2000 et due à la plume de Dario Biagi, l’établissement culturel italien ne pardonne toujours pas à Giuseppe Berto, l’auteur d’ Il cielo è rosso, d’avoir attaqué avec férocité le pouvoir énorme que le centre-gauche résistentialiste s’est arrogé en Italie. C’est donc la conspiration du silence contre cette “vie scandaleuse”.

Quand, en l’an 2000, l’éditeur Bollati Boringhieri a publié la belle biographie de Dario Biagi, La vita scandalosa di Giuseppe Berto, nous nous sommes profondément réjouis et avons espéré que le débat se réamorcerait autour de la figure et de l’oeuvre du grand écrivain de Trévise et que d’autres maisons d’édition trouveraient le courage de proposer à nouveau au public les oeuvres désormais introuvables de Berto, mais, hélas, après quelques recensions fugaces et embarrassées, dues à des journalistes, le silence est retombé sur notre auteur.

Du reste, ce n’est pas étonnant, car à la barre d’une bonne partie des maisons d’édition italiennes, nous retrouvons les disciples et les héritiers de cet établissement culturel de gauche que Berto avait combattu avec courage, quasiment seul, payant le prix très élevé de l’exclusion, de l’exclusion hors des salons reconnus de la littérature, et d’un ostracisme systématique qui se poursuit jusqu’à nos jours, plus de vingt ans après la mort de l’écrivain. La valeur littéraire et historique du travail biographique de Biagi réside toute entière dans le fait d’avoir braqué à nouveau les feux de la rampe sur la vie tumultueuse d’un personnage véritablement anti-conformiste, d’un audacieux trouble-fête. Biagi nous a raconté son histoire d’homme et d’écrivain non aligné, ses triomphes et ses chutes. Il nous en a croqué un portrait fidèle et affectueux: “Berto avait tout pour faire un vainqueur: le talent, la fascination, la sympathie; mais il a voulu, et a voulu de toutes ses forces, s’inscrire au parti des perdants”.

Giuseppe Berto, natif de Mogliano près de Trévise, surnommé “Bepi” par ses amis, avait fait la guerre d’Abyssinie comme sous-lieutenant volontaire dans l’infanterie et, au cours des quatre années qu’a duré la campagne, il a surmonté d’abord une attaque de la malaria, où il a frôlé la mort, et ensuite a pris une balle dans le talon droit. L’intempérance et l’exubérance de son caractère firent qu’il ne se contenta pas de ses deux médailles d’argent et du poste de secrétaire du “Fascio”, obtenu à l’âge de 27 ans seulement… Il cherchait encore à faire la guerre et, au bout de quelques années, passant sous silence un ulcère qui le tenaillait, réussit à se faire enrôler une nouvelle fois pour l’Afrique où, pendant l’été 1942, l’attendait le IV° Bataillon des Chemises Noires. Avec l’aile radicale des idéalistes rangés derrière la figure de Berto Ricci, il espérait le déclenchement régénérateur d’une seconde révolution fasciste. Il disait: “Avoir participé avec honneur à cette guerre constituera, à mes yeux, un bon droit à faire la révolution”.

Giuseppe Berto, natif de Mogliano près de Trévise, surnommé “Bepi” par ses amis, avait fait la guerre d’Abyssinie comme sous-lieutenant volontaire dans l’infanterie et, au cours des quatre années qu’a duré la campagne, il a surmonté d’abord une attaque de la malaria, où il a frôlé la mort, et ensuite a pris une balle dans le talon droit. L’intempérance et l’exubérance de son caractère firent qu’il ne se contenta pas de ses deux médailles d’argent et du poste de secrétaire du “Fascio”, obtenu à l’âge de 27 ans seulement… Il cherchait encore à faire la guerre et, au bout de quelques années, passant sous silence un ulcère qui le tenaillait, réussit à se faire enrôler une nouvelle fois pour l’Afrique où, pendant l’été 1942, l’attendait le IV° Bataillon des Chemises Noires. Avec l’aile radicale des idéalistes rangés derrière la figure de Berto Ricci, il espérait le déclenchement régénérateur d’une seconde révolution fasciste. Il disait: “Avoir participé avec honneur à cette guerre constituera, à mes yeux, un bon droit à faire la révolution”.

Mais la guerre finit mal pour Berto et, en mai 1943, il est pris prisonnier en Afrique par les troupes américaines et est envoyé dans un camp au Texas, le “Fascist Criminal Camp George E. Meade” à Hereford, où, à peine arrivé, il apprend la chute de Mussolini. Dans sa situation de prisonnier de guerre, il trouve, dit-il, “les conditions extrêmement favorables” pour écrire et pour penser. Il apprend comment trois cents appareils alliés ont bombardé et détruit Trévise le 7 avril 1944, laissant dans les ruines 1100 morts et 30.000 sans abri. Aussitôt, il veut écrire l’histoire de ces “gens perdus”, en l’imaginant avec un réalisme incroyable. Il l’écrit d’un jet et, en huit mois, son livre est achevé. Juste à temps car les Américains changent d’attitude envers leurs prisonniers “non coopératifs”, les obligeant, par exemple, à déjeuner et à rester cinq ou six heures sous le soleil ardent de l’après-midi texan, pour briser leur résistance. Et Berto demeurera un “non coopératif”. Après de longs mois de tourments, il est autorisé à regagner sa mère-patrie.

L’éditeur Longanesi accepte de publier le livre de cet écrivain encore totalement inconnu et, après en avoir modifié le titre, “Perduta gente” (“Gens perdus”), considéré comme trop lugubre, le sort de presse, intitulé “Il sole è rosso”, vers la Noël 1946. Berto a confiance en son talent mais sait aussi quelles sont les difficultés pratiques que recèle une carrière d’écrivain; il commence par rédiger des scénarios de film, ce qu’il considère comme un “vil métier”, afin de lui permettre, à terme, de pratiquer le “noble métier” de la littérature. “Il sole è rosso” connaît un succès retentissant, les ventes battent tous les records en Italie et à l’étranger, en Espagne, en Suisse, en Scandinavie, aux Etats-Unis (20.000 copies en quelques mois) et en Angleterre (5000 copies en un seul jour!). On définit le livre comme “le plus beau roman issu de la seconde guerre mondiale”. En 1948, c’est la consécration car Berto reçoit le prestigieux “Prix Littéraire de Florence”. En 1951, toutefois sa gloire décline en Italie. Son roman “Brigante” demeure ignoré de la critique, alors qu’aux Etats-Unis, il connaît un succès considérable (avec “Il sole è rosso” et “Brigante”, Berto vendra Outre Atlantique deux millions de livres) et le “Time” juge le roman “un chef-d’oeuvre”. Les salons littéraires italiens, eux, ont décidé de mettre à la porte ce “parvenu”, en lui collant l’étiquette de “fasciste nostalgique” et en rappellant qu’il avait refusé de collaborer avec les alliés, même quand la guerre était perdue pour Mussolini et sa “République Sociale”. Biagi nous rappelle cette époque d’ostracisme: “Berto, homme orgueilleux et loyal, refuse de renier ses idéaux et contribue à alimenter les ragots”. Berto ne perd pas une occasion pour manifester son dédain pour ceux qui, subitement, ont cru bon de se convertir à l’antifascisme et qu’il qualifie de “padreterni letterari”, de “résignés de la littérature”. Il s’amuse à lancer des provocations goliardes: “Comment peut-on faire pour que le nombre des communistes diminue sans recourir à la prison ou à la décapitation?”. Il prend des positions courageuses, à contre-courant, à une époque où “le brevet d’antifasciste était obligatoire pour être admis dans la bonne société littéraire” (Biagi).

En 1955, avec la publication de “Guerra in camicia nera” (“La guerre en chemise noire”), une recomposition de ses journaux de guerre, il amorce lui-même sa chute et provoque “sa mise à l’index par l’établissement littéraire”. Berto déclare alors la guerre au “Palazzo” et se mue en un véritable censeur qui ne cessait plus de fustiger les mauvaises habitudes littéraires. La critique le rejette, comme s’il n’était plus qu’une pièce hors d’usage, ignorant délibérément cet homme que l’on définira plus tard comme celui “qui a tenté, le plus honnêtement qui soit, d’expliquer ce qu’avait été la jeunesse fasciste”. Et la critique se mit ensuite à dénigrer ses autres livres. Etrange destin pour un écrivain qui, rejeté par la critique officielle, jouissait toutefois de l’estime de Hemingway; celui-ci avait accordé un entretien l’année précédente à Venise à un certain Montale, qui fut bel et bien interloqué quand l’crivain américain lui déclara qu’il appréciait grandement l’oeuvre de Berto et qu’il souhaitait rencontrer cet écrivain de Trévise. Ses activités de scénariste marquent aussi le pas, alors que, dans les années antérieures, il était l’un des plus demandés de l’industrie cinématographique. Le succès s’en était allé et Berto retrouvait la précarité économique. Et cette misère finit par susciter en lui ce “mal obscur” qu’est la dépression. L’expérience de la dépression, il la traduira dans un livre célèbre qui lui redonne aussitôt une popularité bien méritée.

En 1955, avec la publication de “Guerra in camicia nera” (“La guerre en chemise noire”), une recomposition de ses journaux de guerre, il amorce lui-même sa chute et provoque “sa mise à l’index par l’établissement littéraire”. Berto déclare alors la guerre au “Palazzo” et se mue en un véritable censeur qui ne cessait plus de fustiger les mauvaises habitudes littéraires. La critique le rejette, comme s’il n’était plus qu’une pièce hors d’usage, ignorant délibérément cet homme que l’on définira plus tard comme celui “qui a tenté, le plus honnêtement qui soit, d’expliquer ce qu’avait été la jeunesse fasciste”. Et la critique se mit ensuite à dénigrer ses autres livres. Etrange destin pour un écrivain qui, rejeté par la critique officielle, jouissait toutefois de l’estime de Hemingway; celui-ci avait accordé un entretien l’année précédente à Venise à un certain Montale, qui fut bel et bien interloqué quand l’crivain américain lui déclara qu’il appréciait grandement l’oeuvre de Berto et qu’il souhaitait rencontrer cet écrivain de Trévise. Ses activités de scénariste marquent aussi le pas, alors que, dans les années antérieures, il était l’un des plus demandés de l’industrie cinématographique. Le succès s’en était allé et Berto retrouvait la précarité économique. Et cette misère finit par susciter en lui ce “mal obscur” qu’est la dépression. L’expérience de la dépression, il la traduira dans un livre célèbre qui lui redonne aussitôt une popularité bien méritée.

Mais il garde l’établissement culturel dans son collimateur et ne lâche jamais une occasion pour attaquer “l’illustre et omnipotent Moravia”, grand prêtre de cette intelligentsia, notamment en 1962 lorsqu’est attribué le second Prix Formetor. Ce prix, qui consistait en une somme de six millions de lire, et permettait au lauréat d’être édité dans treize pays, avait été conféré cette fois-là à une jeune femme de vingt-cinq ans, Dacia Maraini, que Moravia lui-même avait appuyée dans le jury; Moravia avait écrit la préface du livre et était amoureux fou de la jeune divorcée et vivait avec elle. Au cours de la conférence de presse, qui suivit l’attribution du Prix, Berto décide de mettre le feu aux poudres, prend la parole et démolit littéralement le livre primé, tout en dénonçant “le danger de corruption que court la société littéraire, si ceux qui jugent de la valeur des oeuvres relèvent désormais d’une camarilla”; sous les ovations du public, il crie à tue-tête “qu’il est temps d’en finir avec ces monopoles culturels protégés par les journaux de gauche”. Toute l’assemblée se range derrière Berto et applaudit, crie, entame des bagarres, forçant la jeune Dacia Maraini à fuir et Moravia à la suivre. Berto n’avait que mépris pour celui qu’il considérait comme “un chef mafieux dans l’orbite culturelle” (comme le rappelle Biagi), comme un “corrupteur”, comme un “écrivain passé de l’érotisme à la mode au marxisme à la mode”. En privé, une gand nombre de critiques reconnaissaient la validité des jugements lapidaires posés par Berto, mais peu d’entre eux osèrent s’engager dans un combat contre la corruption de la littérature et Moravia, grâce à ces démissions, récupéra bien rapidement son prestige.

Entretemps, Berto avait surmonté sa crise existentielle et était retourné de toutes ses forces à l’activité littéraire, sans pour autant abandonner ses activités journalistiques où il jouait le rôle de père fouettard ou de martin-bâton, en rédigeant des articles littéraires et des pamphlets incisifs, décochés contre ses détracteurs. “Male oscuro” a connu un succès inimaginable: en quelques mois, on en vend 100.000 copies dans la péninsule et son auteur reçoit le Prix Strega. Berto a reconquis son public, ses lecteurs le plébiscitent mais, comme il fallait s’y attendre, “la critique radicale de gauche le tourne en dérision, minimise la valeur littéraire de ses livres et dénature ses propos”. Ainsi, Walter Pedullà met en doute “l’authenticité du conflit qui avait opposé Berto à son père” et la sincérité même de “Male oscuro” alors que la prestigieuses revue américaine “New York Review of Books” avait défini ce livre comme l’unique ouvrage d’avant-garde dans l’Italie de l’époque. “Mal oscuro”, de plus, gagne deux prix en l’espace d’une semaine, le Prix Viareggio et le Prix Campiello.

Berto a retouvé le succès mais, malgré cela, il ne renonce pas au ton agressif qui avait été le sien dans ses années noires, notamment dans les colonnes du “Carlino” et de la “Nazione” et, plus tard, du “Settimanale” de la maison Rusconi, tribune du haut de laquelle il s’attaque “aux hommes, aux institutions et aux mythes”. En 1971, Berto publie un pamphlet “Modesta proposta per prevenire” qui, malgré les recensions négatives de la critique, se vend à 40.000 copies en quelques mois. Si on relisait ce pamphlet aujourd’hui, du moins si un éditeur trouvait le courage de le republier, on pourrait constater la lucidité de Berto lorsqu’il donnait une lecture anticonformiste et réaliste de la société italienne de ces années-là. On découvrirait effectivement sa clairvoyance quand il repérait les mutations de la société italienne et énonçait les prospectives qu’elles rendaient possibles. Déjà à l’époque, il dénonçait notre démocratie comme une démocratie bloquée et disait qu’au fascisme, que tous dénonçaient, avait succédé un autre régime basé sur la malhonnêteté. Il stigmatisait aussi la “dégénérescence partitocratique et consociative de la vie politique italienne” et, toujours avec le sens du long terme, annonçait l’avènement du fédéralisme, du présidentialisme et du système électoral majoritaire. Il jugeait, et c’était alors un sacrilège, la résistance comme “un phénomène minoritaire, confus et limité dans le temps, … rendu possible seulement par la présence sur le sol italien des troupes alliées”. Pour Berto, c’était le fascisme, et non la résistance, “qui constituait l’unique phénomène de base national-populaire observable en Italie depuis le temps de César Auguste”.

Lors d’une intervention tenue pendant le “Congrès pour la Défense de la Culture” à Turin, sous les auspices du MSI, Berto se déclare “a-fasciste” tout en affirmant qu’il ne tolérait pas pour cela l’antifascisme car, “en tant que pratique des intellectuels italiens, il est terriblement proche du fascisme… l’antifascisme étant tout aussi violent, sinon plus violent, coercitif, rhétorique et stupide que le fascisme lui-même”. Berto désignait en même temps les coupables: “les groupes qui constituent le pouvoir intellectuel... tous liés les uns aux autres par des principes qu’on ne peut mettre en doute car, tous autant qu’ils sont, se déclarent démocratiques, antifascistes et issus de la résistance. En réalité, ce qui les unit, c’est une communauté d’intérêt, de type mafieux, et la RAI est entre leurs mains, de même que tous les périodiques et les plus grands quotidiens… Si un intellectuel ne rentre pas dans un de ces groupes ou en dénonce les manoeuvres, concoctées par leurs chefs, il est banni, proscrit. De ses livres, on parlera le moins possible et toujours en termes méprisants… On lui collera évidemment l’étiquette de ‘fasciste’, à titre d’insulte”. Dans son intervention, Berto conclut en affirmant “qu’en Italie, il n’y a pas de liberté pour l’intellectuel”.

On se doute bien que la participation à un tel congrès et que de telles déclarations procurèrent à notre écrivain de solides inimitiés. Aujourd’hui, plus de vingt ans après sa mort, il continue à payer la note: son oeuvre et sa personne subissent encore et toujours une conspiration du silence, qui ne connaît aucun précédent dans l’histoire de la littérature italienne.

Roberto ALFATTI APPETITI.

(article paru dans le magazine “Area”, Rome, Anno V, n°49, juillet-août 2000; trad. franç.: Robert Steuckers, novembre 2009).

00:15 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (11) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres italiennes, littérature italienne, italie, années 40, années 50, fascisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Paul MODAVE :

L’art et la guerre : de Céline à H. G. Wells

Article paru dans « Le Soir », Bruxelles, le 18 juillet 1944

Au moment où l’invasion et les bombardements aériens dévastent les cités d’art de l’Occident, l’hebdomadaire français « la gerbe » vient d’ouvrir une enquête auprès des personnalités représentatives des lettres françaises afin d’offrir à celles-ci l’occasion de manifester leur réaction devant le saccage du pays.

Ce qui frappe dans beaucoup de ces réponses, c’est leur réticence. Ainsi M. de Montherlant ne voit dans cette enquête qu’une « recherche académique ». M. Georges Ripert, doyen de la Faculté de Droit de Paris, regrette que « dirigeant une maison où il y a beaucoup de jeunes gens, il lui soit impossible d’accorder d’interview » ; quant à Ferdinand Céline, il répond sans ambages « qu’il donnerait toutes les cathédrales du monde pour arrêter la tuerie », ce qui est une plaisante façon de ne rien dire.

Ce qui frappe dans beaucoup de ces réponses, c’est leur réticence. Ainsi M. de Montherlant ne voit dans cette enquête qu’une « recherche académique ». M. Georges Ripert, doyen de la Faculté de Droit de Paris, regrette que « dirigeant une maison où il y a beaucoup de jeunes gens, il lui soit impossible d’accorder d’interview » ; quant à Ferdinand Céline, il répond sans ambages « qu’il donnerait toutes les cathédrales du monde pour arrêter la tuerie », ce qui est une plaisante façon de ne rien dire.

Commentant cette enquête dans « L’Echo de la France », M. Robert Brasillach s’exprime en ces termes : « Les professionnels de l’art savent bien, Céline aussi bien entendu, que la destruction des cathédrales ou des palais n’arrêtera pas pour cela la tuerie. Mais voilà, dire qu’on désapprouve —ce serait bien timide cependant— la destruction inutile de la beauté du monde, c’est donner des gages à l’Allemagne, paraît-il ! On a passé trente, quarante ans à discuter sur l’art et à plaindre nos civilisations mortelles, mais lorsque les trésors de cet art sont renversés par le souffle des machines à détruire, on se tait. On dira ce que l’on pense après la guerre, bien sûr, nuancé à la couleur du vainqueur, s’il y a un vainqueur et s’il y a une après-guerre ».

Et après avoir constaté que le dernier témoignage de liberté d’esprit aura été fourni par les cardinaux de France et de Belgique, M. Brasillach conclut par ses mots : « Aujourd’hui, la parole est aux forces et à leurs rapports. Tout s’est simplifié. Mais on pense seulement que la beauté du monde est chaque jour assassinée, et qu’un univers où risquent de manquer demain, Rouen, Caen, Pérouse, Sienne, Florence, n’est pas un univers dont les artistes, fût-ce par leur silence, aient le droit de se dire fiers. Si le « saint Augustin bouclé », de Benozzo Gozzoli, est détruit, dans ses fresques dorées de San-Gimignano, si la « Charité » ne rayonne plus sur les murailles d’Assise, si, de même qu’on ne peut plus errer au pied des plus nobles façades médiévales de Rostock ou de Hambourg, demain c’est le quai aux Herbes de Gand, qui s’effondre dans le néant où sont déjà les rues rouennaises et les églises de Caen ; et si l’on trouve cela tout naturel et si l’on ne souffre pas dans son cœur de civilisé, alors il me semble qu’on perd le droit de parler de culture et de barbarie, qu’on perd le droit, dans l’avenir, d’affirmer que l’on aime l’Italie, l’art roman, la sculpture française si tendre et si virile, il me semble que le silence qui sert aujourd’hui d’alibi devrait être le silence de toute une vie ».

On ne peut pas mieux dire. Mais dans le même moment où les artistes français se montrent si discrets ou si réticents, l’écrivain anglais H.-G. Wells, dans un article paru dans « Sunday Dispatch », bientôt repris dans le périodique « World Review », exprime ainsi son opinion sur la destruction des monuments d’art de l’Italie : « Dans tout ce territoire, il n’y a pas une seule œuvre d’art, à l’exception peut-être de manuscrits pouvant être mis facilement à l’abri, qui ne puisse être entièrement détruite, et l’héritage de l’humanité n’en éprouvera pas la moindre perte en beauté. Nous possédons notamment les maquettes de toutes ces statues qui peuvent être copiées, y compris leur patine ».

J’espère que nos lecteurs auront savouré comme il convient l’humour —hélas ! inconscient— de M. H.-G. Wells. Mais il ne s’agit pas d’une boutade. Pour l’auteur, auteur particulièrement sérieux mais aussi évidemment privé du sens de l’art que l’aveugle du sens des couleurs, ne comptent que les statues cataloguées dont on possède les maquettes ! La qualité originale d’une œuvre, le milieu spirituel dont elle fait partie intégrante, lui échappe avec une certitude indiscutable. Et il le prouve bien lorsqu’il déclare plus loin, avec autant de pédantisme béat que de solennelle bêtise : « L’art et le goût de l’art sont de suprêmes offenses au charme inépuisable des créations de la nature ».

Alors qu’il n’est que trop évident que l’art est exactement le contraire, c’est-à-dire une action de grâce, un cri d’amour et de reconnaissance devant la beauté de la vie !

Au pays basque, au déclin d’une belle journée, il n’est pas rare que des couples de paysans se mettent, en pleine campagne, à danser et à chanter, pour rien, pour personne, pour la joie de vivre. L’art n’est pas autre chose, à l’origine, que ce chant et cette danse. Mais revenons à M. Wells, qui se hâte d’ajouter : « L’œil embrasse plus de beauté en contemplant un oiseau qui plane, un poisson qui s’ébat dans l’eau, les reflets dans une chute d’eau ou toutes les ombres qui se dessinent sous les branches d’un arbre éclairé par le soleil que nous, misérables gâcheurs, puissions espérer imaginer ou imiter ».

Certes. Mais selon le mot de Debussy : « Les gens n’admettent jamais que la plupart d’entre eux n’entendent ni ne voient » et c’est le rôle de l’artiste de leur ouvrir les oreilles et les yeux à la beauté du monde. Il est trop facile, presque élémentaire, d’énumérer ici ce que chaque artiste nous enseigne au premier coup d’œil : Rubens, la joie triomphante de vivre ; Renoir, la beauté rayonnante de la créature humaine ; Vermeer de Delft, le charme profond des intérieurs où se jouent les lumières et les ombres ; Chardin, la secrète poésie qui vit au cœur des plus humbles objets, des plus usuels. Tout cela et bien davantage encore…

Je sais, hélas ! qu’il n’en est plus ainsi : que ces échanges permanents entre la vie et l’art ne nous sont plus sensibles ; que l’art, né spontanément de la vie, a cessé de nous y ramener avec des facultés plus vives et plus aigües. Les esthètes restent confinés dans un étouffant esthétisme qui n’a d’autre fin que lui-même. Les « viveurs », si je puis les appeler ainsi, ceux qui « vivent leur vie » comme ils disent, m’apparaissent aussi peu soucieux de la beauté des oiseaux qui planent que de la grâce des poissons qui s’ébattent, n’en déplaise à M. Wells. Qu’est-ce que cela veut dire sinon que l’homme a cessé de mettre en jeu toutes ses facultés, de vivre pleinement ? C’est là une des raisons les plus profondes de notre décadence.

Céline, contempteur du monde moderne, pas plus que Wells qui s’en fait l’apologiste, n’y ont trouvé de remède. C’est que l’un et l’autre appartiennent à différents égards, à cette décadence que le Docteur Carrel a si bien diagnostiquée : « Nous cherchons à développer en nous l’intelligence. Quant aux activités non intellectuelles de l’esprit, telles que le sens moral, le sens du beau et surtout le sens du sacré, elles sont négligées de façon presque complète. L’atrophie de ces qualités fondamentales fait de l’homme moderne un être spirituellement aveugle ».

Et, pour revenir au sujet de cet article, cela explique bien des erreurs de jugement, bien des réticences, bien des silence…

Paul Modave.

00:15 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : deuxième guerre mondiale, seconde guerre mondiale, céline, littérature française, lettres françaises, lettres, littérature, histoire, brasillach, 1944, années 40 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

14:26 Publié dans Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature françaises, années 40, deuxième guerre mondiale, seconde guerre mondiale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: Deltastichting - Nieuwsbrief nr. 29 - November 2009

Ex: Deltastichting - Nieuwsbrief nr. 29 - November 2009 Zoals zovele kunstenaars ging Le Corbusier dus ook in de richting van de Sojet-Unie zoeken, aangetrokken als hij was door het grootse, zelfs megalomane van de economische 5-jaarplannen. De architect stond in die tijd in rechtse kringen bekend als “saloncommunist” en “fakkel van Moskou”. Raar toch dat het Zwitserse weekblad hier géén commentaar moet ventileren…

Zoals zovele kunstenaars ging Le Corbusier dus ook in de richting van de Sojet-Unie zoeken, aangetrokken als hij was door het grootse, zelfs megalomane van de economische 5-jaarplannen. De architect stond in die tijd in rechtse kringen bekend als “saloncommunist” en “fakkel van Moskou”. Raar toch dat het Zwitserse weekblad hier géén commentaar moet ventileren…

00:20 Publié dans Architecture/Urbanisme | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : architecture, urbanisme, suisse, france, fascisme, années 30, années 40, ville |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Innerlichkeit und Staatskunst -

Innerlichkeit und Staatskunst -

Zum Wirken Friedrich Hielschers

"Zwei Tyrannen tun dem Deutschen not: ein äußerer, der ihn zwingt, sich der Welt gegenüber als Deutscher zu fühlen, und ein innerer, der ihn zwingt, sich selbst zu verwirklichen."

- Ernst Jünger

Verfasser: Richard Schapke

Der am 7. März 1990 auf dem Rimprechtshof im Schwarzwald verstorbene Friedrich Hielscher gehörte mit Sicherheit zu den originellsten Ideologen der Konservativen Revolution. Da er sich nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg noch weniger als ohnehin schon um öffentliche Breitenwirkung scherte, gerieten seine Arbeiten in fast vollständige Vergessenheit, auch wenn Hielschers Name des öfteren in Jüngers "Strahlungen" auftaucht. In jüngster Zeit ist eine regelrechte Wiederentdeckung des unkonventionellen Nietzscheaners zu bemerken - Grund genug für einen Versuch, sich Friedrich Hielschers Leben und Werk zu nähern. Wir greifen hierbei oftmals auf Originalzitate zurück, um den Gegenstand unserer Betrachtung in seinen eigenen Worten sprechen zu lassen. Mitunter sind Zitate und Analysen aus der nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg veröffentlichten Autobiographie "Fünfzig Jahre unter Deutschen" eingeflochten. Aus inhaltlichen Gründen gehen wir hierbei von der Chronologie der Veröffentlichung ab.

1. Herkunft

Friedrich Hielscher wurde am 31. Mai 1902 in Guben (nach anderen Angaben in Plauen/Vogtland) in eine nationalliberale Kaufmannsfamilie hineingeboren. Gerade 17 Jahre alt geworden, absolvierte er sein Kriegsabitur am Humanistischen Gymnasium, um sich fast unmittelbar darauf einem der gegen Spartakisten und Separatisten oder in den Grenzkämpfen im Osten fechtenden Freikorps anzuschließen. Dieses Freikorps Hasse ging im Juni 1919 aus der MG-Kompanie des ehemaligen Infanterieregiments 99 hervor und kam in Oberschlesien gegen polnische Insurgenten zum Einsatz. Zu den Freikorpskameraden Hielschers gehörte Arvid von Harnack, der später durch seine Mitarbeit in Harro Schulze-Boysens Roter Kapelle zu Berühmtheit gelangen sollte. Die Einheit bewährte sich und wurde in die Reichswehr übernommen, aber Hielscher quittierte den Dienst im März 1920, da er eine Beteiligung am überstürzten Kapp-Putsch gegen die Republik ablehnte.

Es folgte ein Jurastudium in Berlin, das von regelmäßigen Besuchen an der Hochschule für Politik begleitet wurde. Dem Brauch entsprechend schloß Hielscher sich einer Studentenverbindung an und wählte die Normannia Berlin. Nach einer vorübergehenden Mitgliedschaft im Reichsclub der nationalliberalen Deutschen Volkspartei (DVP) traten in Gestalt des aus der SPD hervorgegangenen nationalen Sozialisten August Winnig und des Geschichtsphilosophen Oswald Spengler prägendere politische Einflüsse an ihn heran. Von Winnig übernahm Hielscher die Überzeugtheit von einer weltgeschichtlichen Mission Deutschlands, vom Spengler das zyklische Geschichtsbild. Hinzu kam das in den Werken Ernst Jüngers herausgearbeitete Kriegertum.

Im Jahr 1924 erfolgte der Wechsel nach Jena, wo Hielscher das Referendarexamen bestand und im Dezember 1926 mit Auszeichnung zum Doktor beider Rechte promovierte. Die ungeliebte Beschäftigung als Verwaltungsjurist im preußischen Staatsdienst wurde nach nicht einmal einem Jahr im November 1927 aufgegeben. Die Anforderungen des Studiums behinderten nicht den häufigen Besuch des Weimarer Nietzsche-Archivs. Friedrich Nietzsche sollte dann auch über seine Schwester Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche der letzte wirklich prägende Bestandteil des sich allmählich herauskristallisierenden Weltbildes sein. Von Dauer war die weitere Beteiligung als Alter Herr am Verbandsleben der Normannia Berlin, wo Hielscher die Bekanntschaft von Persönlichkeiten wie Horst Wessel, Hanns Heinz Ewers und Kurt Eggers machte.

2. Innerlichkeit

Am 26. Dezember 1926 betrat Friedrich Hielscher mit dem Aufsatz "Innerlichkeit und Staatskunst" die Bühne der politischen Publizistik. Der junge Jurist hatte sich auf Rat Winnigs dem nationalrevolutionären Kreis um die Wochenzeitung "Arminius" angeschlossen, dem nicht zuletzt Ernst Jünger das Gepräge gab. Aus der Begegnung mit Jünger entstand eine lebenslange Freundschaft. "Innerlichkeit und Staatskunst" enthält bereits alle wesentlichen Aspekte des Hielscherschen Weltbildes und soll daher ausführlicher dokumentiert werden.

"Seien wir ehrlich: wir stehen nicht am Beginn eines neuen Aufstieges, sondern vor dem Ende des alten Zusammenbruches. Dieses Ende liegt noch vor uns. Wir müssen erst noch durch das Schlimmste hindurch, ehe wir ans neue Werk gehen können. Jeder, der jetzt schon mit irgendeinem Aufbau beginnt, tut sinnlose Arbeit. Das will folgendes heißen. Jede kriegerische Vorbereitung, die auf einen Befreiungskrieg in der Gegenwart oder der nahen Zukunft abzielt, ist wertlose Spielerei und grob fahrlässige Dummheit. Jeder geistige Versuch, einigende Bünde, Verbände, kulturelle Vereinigungen, Weisheitsschulen, oder wie man das Zeug sonst nennen mag, in der Gegenwart zu gründen, ist Selbstbetrug und Unehrlichkeit der inneren Haltung.

"Seien wir ehrlich: wir stehen nicht am Beginn eines neuen Aufstieges, sondern vor dem Ende des alten Zusammenbruches. Dieses Ende liegt noch vor uns. Wir müssen erst noch durch das Schlimmste hindurch, ehe wir ans neue Werk gehen können. Jeder, der jetzt schon mit irgendeinem Aufbau beginnt, tut sinnlose Arbeit. Das will folgendes heißen. Jede kriegerische Vorbereitung, die auf einen Befreiungskrieg in der Gegenwart oder der nahen Zukunft abzielt, ist wertlose Spielerei und grob fahrlässige Dummheit. Jeder geistige Versuch, einigende Bünde, Verbände, kulturelle Vereinigungen, Weisheitsschulen, oder wie man das Zeug sonst nennen mag, in der Gegenwart zu gründen, ist Selbstbetrug und Unehrlichkeit der inneren Haltung.

(...) Beweise haben in der Welt der Tatsachen keinen Sinn.. Es ist noch nie vorgekommen, daß man politische Gegner durch Beweise bekehrt oder in ihrer Stellung erschüttert hätte. Aber es ist nötig, daß die sich einig werden, die im Grunde ihres Wesens Träger ein und desselben Zieles sind: des heiligen Deutschen Reiches. Zu dieser Einigung bedarf es des gegenseitigen Verständnisses. Dieses Verständnis fehlt. Ihm dient die folgende Begründung. Sie bildet sich nicht ein, daß an dem kommenden deutschen Zerfall irgend etwas zu ändern sei. Aber sie ist der Überzeugung, daß es jetzt schon an der Zeit ist, an der geistigen Haltung zu arbeiten, von der aus der spätere Aufbau allein beginnen kann.

Seit die Germanen in Berührung mit der kraftlos gewordenen und überreifen römisch-byzantinisch-christlichen Kulturenvielfalt gekommen sind, die den Ausgang des sogenannten Altertums bildet, ist ihre innere Haltung unfrei. Seit sie das Denken dieser fremden Welten übernommen haben, unfähig, die kaum zum Ausdruck gekommene eigene Art gegen das jeder Unmittelbarkeit längst entwachsene, zu Ende gedachte fremde Wesen zu schützen, seit dieser Zeit ist die deutsche Haltung zweispältig (sic!). Der Deutsche bejaht den Kampf als solchen; aber die müde Sittlichkeit der Fremden sucht den Frieden. Seit also der deutsche Geist überfremdet ist, wird jede deutsche Kampfhandlung mit schlechtem Gewissen getan, wird halb, kommt nicht zum endgültigen Erfolge und sinkt nach oft prachtvollem Aufschwung immer wieder in sich zusammen. Staatskunst ist die Fähigkeit, die eigenen Kampfhandlungen mit dauerndem Erfolg nach außen zu verwirklichen. Seit der Deutsche überfremdet ist, steht die deutsche Staatskunst allein und hat die deutsche Innerlichkeit nicht geschlossen hinter sich. (...)

Mit Bismarcks Entlassung verwandelte sich das Bismärckische Reich in den Wilhelminischen Staat, in ein Verfassgebilde, dessen Untergang unvermeidbar war. Diese Unvermeidbarkeit zeigte sich im Weltkriege. Wenn kriegerisches Heldentum ein Schicksal wenden kann, dann mußten wir siegen. Aber wir mußten die Fahnen senken, weil hinter dem deutschen Krieger nicht die deutsche Heimat stand als eine Einheit innerlichsten Glaubens, Wollens, Denkens, als eine Welt der ungetrübten reinen und abgrundtiefen Zuversicht. So kam die Niederlage. Der Staat der Weimarer Verfassung ist nicht ein neues Gebilde, das von seinem Vorgänger irgendwie wesentlich verschieden wäre, sondern nur die letzte Gestalt des Wilhelminischen Staates, die dessen alberne, wertlose, erbärmliche Seiten in vorbildlicher Deutlichkeit und - freilich unbewußter - Ehrlichkeit zeigt.

So ist hier nichts mehr zu halten und zu retten. Je eher dieser Staat zugrunde geht, um so besser ist es für die deutsche Sache. Sein weiteres Schicksal ist uns vollendet gleichgültig. Soll ich noch deutlicher werden? Also ist hier nichts mehr zu verbessern. Wenn das noch möglich wäre, dann würde zudem nicht das kindische Hurraschreien scheinkriegerischer Aufzüge von Wert sein, sondern einzig und allein ein verbissenes, unterirdisches, schweigendes und selbstverleugnendes Arbeiten, das vom Kleinsten anfängt, wie Friedrich Wilhelm der Erste angefangen hat. Aber weil es nicht möglich ist, an diesem Staat noch Hand anzulegen, bleibt nur eins übrig: in sich zu gehen, und aus der Tiefe des eigenen Herzens die Zuversicht, den Glauben heraufzuholen, der die deutsche Zukunft tragen und ohne den das neue Werk nicht begonnen werden wird. (...)"

Wir fassen zusammen: Der Zusammenbruch der liberalkapitalistischen Ordnung ist nicht in vollem Gange, sondern er steht erst noch bevor. Vor diesem Kollaps sind jede Aufbauarbeit und jede politische Partizipation zwecklos. Das deutsche Wesen wurde vom westlich-christlichen Materialismus überfremdet, und daher war die Niederlage des verwestlichten Kaiserreiches im Weltkrieg unvermeidbar. Die Republik ist die Fortsetzung des wilhelminischen Staates in anderem Gewande und ebenso wie er dem Untergang geweiht.

Am 30. Januar 1927 legte Hielscher den Aufsatz "Der andere Weg" nach: "Will ein unterworfenes Volk frei werden, so muß es dazu zweierlei tun: es muß erstens innerlich einig werden und zweitens seine staatskünstlerische Begabung betätigen...Für die Betätigung unserer staatskünstlerischen Begabung fehlen uns die Mittel." Der Hauptfeind waren nicht die unterdrückten asiatischen Völker, sondern die "Träger der europäischen Zivilisation...Aber wir bestreiten, daß wir zur Freiheit, d.h. zum selbstherrlichen Gebrauch unserer eigenen Kräfte gelangen können, ohne in entscheidenden Gegensatz zu Europa zu treten...Daher ist es geboten, unsere ganzen Fähigkeiten auf den anderen Weg zu richten, dessen Begehung ebenfalls unumgänglich notwendig ist, auf die endliche Einigung des deutschen Geistes." Angezeigt ist die "mephistophelische Schlangenhaftigkeit und Gewandtheit in der Verschleierung der tiefsten Gründe und Hintergründe". In diesem Kampf sind alle Mittel erlaubt, solange man die eigene Treue nicht verletzt. "Ersichtlich setzt eine solche Handlungsweise eine Sicherheit der inneren Haltung voraus, die kaum überbietbar ist." Der geistige Kampf gilt nicht etwa der etwaigen Undurchsichtigkeit des Handelns, sondern der Vielfältigkeit der fremden Einflüsse. Einzig auf eigenen Willen gegründet ist die Welt eines neuen Geistes, einer machtwilligen Seele zu errichten. "Das ist das Ziel. Der Weg zu ihm führt über eine rücksichtslose strenge Selbsterziehung eines jeden Einzelnen. Er führt über das eindeutige Bekenntnis zu dem Glauben, an den sich die Dichter der alten Sagen, an den sich Eckehart, Luther, Goethe und Nietzsche hingegeben haben. Er führt über die Gestaltung jener Erziehung aus diesem Glauben heraus zur Züchtung eines Geschlechts, das im Opferdienst am deutschen Glauben einig und deshalb, und nur deshalb, berufen ist, das staatskünstlerische Werk zu vollbringen, zu dem die Gegenwart ebensowohl aus einem Mangel an äußerem Willen wie aus innerer Glaubenslosigkeit nicht geeignet ist."

Am 13. Februar 1927 folgte "Die faustische Seele": "Die seelische Zugehörigkeit zum Deutschtum ist das Grunderlebnis der deutschen Menschen. Der letzte große Versuch, sich mit diesem Grunderlebnis im Bewußtsein auseinanderzusetzen, ist Spenglers Lehre von der faustischen Kultur. Der deutsche ist der faustische Mensch. Die faustische Kultur ist das deutsche Seelentum. Spengler sieht es aus dem unendlichkeitsverlorenen Walhall mit seinen tiefen Mitternächten herabsteigen in die Tiefen der Mystik, sieht es zu endlosen Kämpfen, gleichgültig gegen den Tod, das Schwert ziehen, die gotischen Dome wollen den Himmel stürmen, der lutherische Bauerntrotz schlägt drein, ins Grenzenlose schreitet die wälderhafte nordische Musik, unter den zartesten und weltseligsten Melodien ihre gewaltige Einsamkeit verbergend oder sie hinausschreiend in Sturm und Gewitter, aus Not und Elend und Blut steigt das Preußentum empor, und als dem Faust der Zarathustra folgt, erschüttern Wagners Posaunen die Welt und der Preuße Bismarck holt die Krone aus dem Rhein. Dann folgt der Zusammenbruch, und von neuem beginnt der alte Kampf (...)

Ich sehe einen langen Weg. Im Urdämmer der Sage stehen der deutsche Machtwille und die deutsche Innerlichkeit zueinander und sind untrennbar verbunden....Friedrich Nietzsche, der letzte große Träger der deutschen Innerlichkeit, hat den Willen zur Macht gelehrt und so die alte Weisheit wieder geweckt, die von den Tagen der Götter, von den Tagen Sigfrids und Hagens her die deutsche Sittlichkeit verkündet. Wenn unsere Innerlichkeit wieder gelernt haben wird, ihr zu folgen, wenn der deutsche Machtwille nicht mehr alleinstehen wird, erst dann, aber dann sicher, wird die deutsche Zwietracht aufhören, wird sich das deutsche Menschentum vollenden und in seiner Vollendung heimfinden zu dem ewigen Brunnen, aus dem es entstiegen ist."

Verdeutlicht wird diese Darstellung der faustischen Seele durch den Aufsatz "Die Alten Götter". Sagen, Märchen und die germanisch-keltische Mythologie bilden die Heimat der deutschen Seele. Hielscher betont den Kampf als Daseinsprinzip: "Das versteht nur ein Deutscher, daß man sich gegenseitig die tiefsten Wunden schlagen und dennoch die beste Freundschaft halten kann. Denn der Deutsche ist in seinem Innern selber so: hundert- und tausendfältig zerrissen, ein Schlachtgebiet aller holden und unholden Geister, und aus dieser Zerrissenheit seinen Stolz herausholend und eine höhere Einheit, die über allem Ernste sich ein Lächeln bewahrt hat, und über allen Abgründen eine einsame und lichte Höhe, die ihren Glanz in alle Tiefen schickt....Der Kampf ist das Nein, und die Vollendung ist das Ja. Die Geburt des Ja aus dem Nein, die Vollendung im Kampfe, das ist das Lied von den alten Göttern. Es ist das Lied, das alle großen Träger der deutschen Innerlichkeit verkündet haben. Wenn Eckehart die brennende Seele lehrte, in der doch eine ungetrübte schweigende Stille herrscht, wenn Luther im Wirken und durch das Wirken Satans die Allmacht Gottes geschehen sah, wenn Goethe alles Drängen und Ringen als ewige Ruhe in Gott erlebte, wenn endlich Nietzsches Welt des Willens zur Macht, diese Welt des Ewig-sich-selber-Schaffens und Ewig-sich-selber-Zerstörens als endloser Kreislauf zu sich selber guten Willen hatte, so war das immer nur das alte Lied" (der nordischen Mythologie). "So wird der Kampf zum Selbstsinn, und die Treue in diesem Kampfe ist das Höchste. Es gibt nichts anderes. Um des Kampfes willen ist die Innerlichkeit da, weil sie die Kraft zu diesem Kampfe gibt...Das ist eine ganz andere Treue, als die Gegenwart sie kennt. Das ist die Treue, die alles opfert, den Schwur, die Ehre, das eigene Blut; die Treue, die nur das eigene Werk und seine Vollendung im Kampfe kennt."

Das Leben der Völker bemißt sich nach Völkerjahren mit den vier Jahreszeiten. Hielscher zieht zahlreiche Allegorien mit dem Vegetationszyklus eines Baumes. Die Deutschen befinden sich derzeit im Stadium des Winters, ausgelöst durch die "Verstofflichung", den Materialismus der westlichen Zivilisation. Die Entstehung des Materialismus verortet Hielscher bereits zu Zeiten der Renaissance, aus der sich der Frühkapitalismus entwickelte. Der Mensch will nicht mehr gebunden sein, sondern wider seine Natur nur noch von sich selbst abhängen. Religion, Volk, Tradition und Kultur weichen dem Individualismus. Die Menschen haben die Wahl, ob der Winter "die Umkehr oder den Tod bringen (wird), nach unserer Wahl und nach der zukommenden Gnade der Götter".

"Wer die Kälte der Oberfläche ändern wollte, würde als Schwarmgeist scheitern. Desgleichen steht nicht in der Hand der Wurzeln und der Wintersaat und nicht in der Hand des Menschen. Vielmehr ist uns diese Kälte vorgegeben." Jeder Winter birgt den Keim des Frühlings, nicht zuletzt symbolisiert durch die Sonnenwende.

"An der Quelle muß der Strom versiegen, an der Wurzel muß das Unheil absterben. Und in Quelle und Wurzelgrund muß das Heil von neuem gewonnen werden." Das Reich ist noch nicht stark genug, um oberirdisch gedeihen zu können. Es ist verborgen im Inneren seiner Glieder, eines neuen Menschentypus, keine sichtbare Gestalt. Innerlichkeit und Wille zur Macht verknüpfen sich miteinander.

So geht es heute nicht mehr um das Retten des alten abendländischen Leibes, sondern um das Bilden des neuen." Soziale Herkunft und Interessen der Unterirdischen sind gleichgültig. "Und jeder mag unter den Vorbildern sich seinen Helden wählen."

3. Staatskunst

Nachdem Hielscher dergestalt die Notwendigkeit unterstrichen hatte, ein neues Bewußtsein als Grundvoraussetzung erfolgreichen Handelns zu schaffen, wandte er sich außenpolitischen Fragen zu. Im März 1927 veröffentlichte der "Arminius" seinen vielbeachteten Aufsatz "Für die unterdrückten Völker!", der Hielscher gewissermaßen zum Erfinder des Befreiungsnationalismus machen sollte. Wir merken an, daß derartige Gedankengänge auch schon im Werk Moeller van den Brucks auftauchen.

Der Erste Weltkrieg hatte die Völker aller Kontinente aufgerüttelt, so daß jede politische Maßnahme ihre Wirkung verhundertfachte. Auf dem Brüsseler Kongreß der unterdrückten Völker hatten die Farbigen erstmals einmütig ihre Stimme gegen den Westen, gegen Imperialismus und Kolonialismus und für den Nationalismus erhoben. Unter den Bestimmungen des Versailler Diktats war Deutschland mit seiner dem Westen hörigen Demokratie kein souveräner Staat, sondern ebenfalls eine Kolonie. Kein Kontinent stand mehr für sich alleine, sondern neue Aufgaben, Freundschaften und Ziele entwickelten sich. Im Zentrum der Hoffnung Hielschers stand das Erwachen des Giganten China, Indiens oder der arabischen Welt, weniger die Sowjetunion, die ihre "russische" Ideologie allen anderen Völkern aufzwingen wollte und damit kein echter Partner der nach Freiheit strebenden Völker war.

Deutschland ist kein Teil des westlichen Europa, sondern ein Teil des asiatischen Ostens. In der Verehrung des Ostens verbeugt sich der Deutsche "vor einer weiten unendlichen, durchaus uneuropäischen und geheimnisvollen Welt einer sehnsüchtigen und zutiefst ruhigen Weisheit und Selbstsicherheit, aus der er seine Kraft strömen fühle". Die deutsche Innerlichkeit ist ein Widerspruch gegen den Westen und dessen Zivilisationsdenken. "Die Völker des Ostens glauben an unverrückbare Kräfte, denen sie sich verdienstet wissen, aus denen ihre Art entspringt, und zu der sie zurückkehrt, wenn ihre Stunde geschlagen hat. Der Deutsche gehört zum Osten und nicht zum Westen. Der Westen ist Zivilisation, der Osten ist Kultur. Die Zivilisation ist auf dem Gelde und der Berechnung aufgebaut und kennt keine Innerlichkeit. Die Kultur errichtet auf dem Grunde einer unerschütterlichen Gewißheit die Werke einer hohen Kunst, eines demütigen Denkens, einer hingebenden Weisheit. Die Völker des Westens sind Zivilisationsvölker, die Völker des Ostens tragen ihre großen Kulturen."

Im Gegensatz zum kapitalistischen Westen ist der Osten sozialistisch, wobei Sozialismus hier als eine innere Haltung und nicht als theoretisches System zu verstehen ist. Während der Kapitalismus den Menschen seinen Taten entfremdet und dem Nutzen unterwirft, will der Sozialismus die Leistung und das Werk. Die Menschen sind keine Einzelwesen, sondern Glieder von Gemeinschaften. "Der Westen kennt nicht Ideen, sondern Konzerne; er kennt keine Gemeinschaften, sondern wirtschaftliche Verbundenheit."

"Der Westen ist Imperialismus, der Osten ist Nationalismus. Der Nationalismus ist die Folge des Glaubens an die eigene Kultur, der Wille zur Durchsetzung ihrer eigenen Art, der Wille zum Dienst an der Gemeinschaft, die auf der eigenen Kultur beruht. Der Imperialismus ist die Benutzung der nationalen Mittel zur Erlangung wirtschaftlichen Profites, die Umfälschung nationaler Ziele in Wirtschaftsinteressen."

"Wir deutschen Nationalisten werden mit den Nationalisten des Ostens zusammengehen; wir fordern den gemeinsamen Kampf gegen den westeuropäisch-amerikanischen Imperialismus und Siegerkapitalismus, wir fordern die Abkehr der deutschen Wirtschaft von den westlichen Verbundenheiten, die Abkehr der deutschen Geistigkeit vom Westen. Im Osten kämpfen die unterdrückten Völker den gleichen Kampf, den Kampf der Kulturnationen gegen die Zivilisationsvölker, den Kampf der Tiefe gegen die Oberfläche. Verbünden wir uns ihnen. Scheuen wir kein Opfer. Der Osten wartet auf uns. Enttäuschen wir ihn nicht. Wir sind der Vorposten des Ostens gegen den Westen. Der Westen wankt, und der Sturm aus dem Osten hat begonnen. Die deutsche Stunde schlägt."

Hielschers Ausführungen, die sich im übrigen jeder Rassist und Xenophobe einmal etwas intensiver durch den Kopf gehen lassen sollte, trafen auf ein gemischtes Echo. Der Kampfverlag der NS-Parteilinken unterstützte Hielschers internationalistisch-nationalistische Thesen ebenso wie Franz Schauweckers "Standarte". Bezeichnenderweise kam vom hitleristischen "Völkischen Beobachter" und von den Vereinigten Vaterländischen Verbänden schroffe Ablehnung.

Mit seinem philosophisch-politischen Programm stürzte Hielscher sich in die Politik, zunächst eine Reihe geopolitischer Analysen nach obigem Muster im "Arminius" veröffentlichend und jegliche Mitarbeit am Weimarer System heftig kritisierend. Im Juli 1927 beteiligte er sich an der von August Winnig gegründeten Berliner Sektion der Alten Sozialdemokratischen Partei, einer "rechten" Abspaltung der SPD. Als Gruppenorgan fungierte die Zeitschrift "Der Morgen", zu deren Autoren neben Hielscher die Nationalrevolutionäre Eugen Mossakowsky und Karl Otto Paetel gehörten. Anhang aus der Arbeiterschaft konnte kaum gewonnen werden, dafür kamen die bürgerlichen Rebellen.

4. "Das Reich"

Spätestens das ASP-Experiment überzeugte Hielscher von der Sinnlosigkeit tagespolitischer Aktivitäten. In seinen Memoiren "Fünfzig Jahre unter Deutschen" analysiert er die Situation im Nachhinein so: "Will man sich den Ort der Einzelgänger vor Augen führen, so stelle man sich die Parteien als ein Hufeisen vor, an dessen einem Flügel die Nationalsozialisten, an dessen anderem die Kommunisten standen.

Dann finden wir neben den Nationalsozialisten die Deutschnationalen Hugenbergs, neben ihnen die Deutsche Volkspartei Stresemanns und neben ihr das katholische Zentrum, das die Mitte tatsächlich bildete. Links davon sehen wir die Demokraten, hernach die Sozialdemokraten und schließlich die Kommunistische Partei.

Aber mit ihnen schloß sich der Kreis nicht, sondern zwischen ihnen und den Nationalsozialisten klaffte eine Lücke, die sich um so weniger schließen konnte, als die Nationalsozialisten und die Kommunisten bereits nur noch dem Namen nach Parteien waren, in Wirklichkeit aber Horden, und zwar Horden in Bundesgestalt und mit parlamentarischer Maske. Sie wollten Massenbewegungen sein, gaben sich vor ihren gutwilligen Anhängern das Gesicht eines Bundes und spielten nach außen die Partei, um nicht verboten zu werden.

Den Bund kennzeichnet im Aufbau die gegenseitige Verpflichtung zwischen Haupt und Gliedern, im Wesen der Geist, der sie verbindet, sei es nun ein Glaube oder auch nur eine besondere Menschlichkeit, im Sinne der freiwilligen Dienste an diesem Geiste und im Zwecke das Ziel, das er dem Haupte und den Gliedern aufgibt.

Der Horde mangelt im Aufbau die Gegenseitigkeit, im Wesen der Geist, im Sinne der freie Wille und im Zwecke das Ziel. An die Stelle der Gegenseitigkeit tritt der einseitige Gehorsam, an die Stelle des Geistes das Programm, an die Stelle des freien Willens der Zwang und an die Stelle des Zieles der erstrebte Vorteil und Nutzen, sei es des Hordenführers allein, sei es zugleich seiner Garde oder der ganzen Horde.

Die Gestalt des Bundes anzunehmen empfiehlt sich der Horde, wenn das Volk sich wieder nach Bund und Verbundenheit sehnt, weil die Lüge am besten in Gestalt der Wahrheit zu wirken vermag und von ihren abgesplitterten und selbständig genommenen Teilen allein lebt. Mit der Wahrheit zu schwindeln, ist nicht nur die beste, sondern es ist auch die einzige Art der Lüge, die Erfolg haben kann.

Und die Maske der Partei schließlich bietet sich von selber an, weil in Verfallszeiten nicht das Volk, sondern der Bürger herrscht, welcher in den Zweckverbänden der unverbindlichen Parteien sich am besten darzustellen und zu entfalten vermag. (...)

So sehen wir nicht nur an den äußeren Flügeln des Parteienhufeisens zwei offenkundige Horden in Bundesgestalt und mit scheinbündischen Gliederungen wie hier der SA oder der SS und dort dem Rotfrontkämpferbunde, sondern auch bis fast in die Mitte heran jede Partei bemüht, sich eine Horde heranzubändigen oder sich eines Bundes zu versichern. (...)

Zwischen den beiden Hordenflügeln aber kochten die Einzelgänger ihren Trank und bildete sich Bund. Hier schlugen die Flammen von rechts nach links herüber, um der Feuerzange die nötige Glut zu geben."

Auf den Zerfall der "Arminius"-Gruppe folgte ab Oktober 1927 die Zeitschrift "Der Vormarsch", ursprünglich ein Blatt von Kapitän Ehrhardts Wikingbund. Die Schriftleitung lag bei Ernst Jünger und Werner Lass, dem Führer der Schill-Jugend, einem ehemaligen Gefolgsmann des Freikorpsführers Roßbach mit starkem Einfluß in der HJ. Hielscher variierte hier weiterhin seine bekannten Thesen. Der "Vormarsch" wurde zum Zentrum einer bewußt provokativen Militanz. Es kam zur Bildung kleiner revolutionärer Zirkel, die über die Grenzen der Bünde und Parteien zusammenarbeiten. Engere Verbindungen unterhielt der "Vormarsch"-Kreis zur NSDAP, die sich durch ihren sozialrevolutionären Charakter zusehends von den anderen Rechtsverbänden absonderte. Unterhalb der agitatorischen Ebene verkehrte Hielscher in diversen Zirkeln, von denen vor allem der Salon Salinger zu nennen ist. Der jüdischstämmige Hans Dieter Salinger, Beamter im Reichswirtschaftsministerium und Redakteur der "Industrie- und Handelszeitung", versammelte hier einen bunt zusammengewürfelten Kreis um sich. Neben Hielscher sind hier Ernst von Salomon, Hans Zehrer, Albrecht Haushofer, Ernst Samhaber oder Franz Josef Furtwängler, die rechte Hand des Gewerkschaftsführers Leipart, zu nennen.

Im Frühjahr 1928 bildete Friedrich Hielscher, wohl inspiriert durch Salingers Kontaktpool und durch den Schülerkreis des Dichters Stefan George (vor allem in Aufbau und Methode), einen eigenen Zirkel um seine Person. Diesem Kreis fiel beispielsweise indirekt das Verdienst zu, den Brecht-Weggefährten Arnolt Bronnen für die revolutionäre Rechte zu gewinnen. Nach dem Rückzug Jüngers übernahm Hielscher im Juli 1928 gemeinsam mit Ernst von Salomon die Leitung des "Vormarsches", dessen Auflage auf 5000 Exemplare gesteigert werden konnte. Der NS-Studentenbund warb um den unter Studenten und Bündischer Jugend zugkräftigen Intellektuellen, um ihn als Veranstaltungsredner für sich zu gewinnen. Das Verbandsorgan der Ehrhardt-Anhänger und rechten Paramilitärs entwickelte sich zu einer übernational-antiimperialistischen Monatszeitung, die jedoch durch die wirtschaftliche Inkompetenz von Verlagsleiter Scherberning behindert wurde.

Dem Zeugnis Ernst von Salomons zufolge war der Hielscher-Kreis in seiner Anfangsphase jedoch ein Tummelplatz menschlicher Intrigen und Eitelkeiten. Im Herbst 1928 reagierte Hielscher auf die sich abzeichnende Bauernrevolte in Norddeutschland mit der schwächlichen Forderung nach Verminderung der Steuern und einer Agrarreform - offensichtlich hatte er das revolutionär-anarchistische Potential der entstehenden Landvolkbewegung nicht erkannt. Der verärgerte Salomon urteilte im Februar 1929: "Hielscher hat sich für mein Empfinden völlig ausgeschöpft, was er betreibt, ist Leerlauf, schade um ihn. Aber er erkennt das selber nicht, will die Dinge forcieren und erreicht dadurch erst recht nichts. Außerdem führt er einen absonderlichen Lebenswandel, der an seinen Nerven zehrt. Dabei haben die ganzen Leutchen...dickste Illusionen im Kopp..." Hielscher bilde sich ein, "man könne Politik ohne Macht, allein durch Geist und gute Verbindungen machen". Zugleich hielten die heftigen internen Auseinandersetzungen im Hielscher-Kreis mit Intrigen, Verleumdungen und Verdächtigungen an. Salomon kehrte dem "Vormarsch" daraufhin mit der Bemerkung, hier müsse noch einmal "bannig femegemordet" werden, den Rücken und schloß sich den Landvolkterroristen an.

Trotz eines Hitler-Verdikts gegen den "Vormarsch", der angeblich mit dem "asiatischen Bolschewismus" liebäugele, stellte sich der mächtige Gregor Strasser am 25. Oktober 1929 hinter die Gruppe. Ernst Jünger, Franz Schauwecker oder Friedrich Hielscher seien Beispiele für die steigende Tendenz, "daß der Nationalsozialismus beginnt, magnetgleich andere Kreise, andere bisher in ihrer Sphäre festgefügte, gleichwertige Geister an sich zu ziehen." Am gleichen Tag schrieb Hielscher in den "Kommenden": "Stoßen wir also bei unserer nationalistischen Arbeit auf politische Handlungen der russischen Außenpolitik, die gegen den Westen gerichtet sind, so werden wir diese Handlungen begrüßen und nach Möglichkeit fördern. Stoßen wir auf die kommunistische Ideologie selbst, die auf dem dialektischen Materialismus beruht, so werden wir ihr das idealistische Bekenntnis zur Deutschheit entgegenzustellen haben; und wir werden nicht zu vergessen haben, daß der Sozialismus, den wir wünschen, die Unterordnung der Menschen unter den nationalistischen Staat auf wirtschaftlichem Gebiet bedeutet, während der Sozialismus, den Marx anstrebt, das staatenlose, größtmögliche Wohlergehen der größtmöglichen Zahl will."

Im Sommer 1929 legte Hielscher die Chefredaktion des "Vormarsch" nieder, um sich einem eigenen Zeitschriftenprojekt und einem weltanschaulichen Grundlagenwerk zu widmen. Die Monatsschrift "Das Reich" sollte sich zu einem der maßgeblichen Blätter der nationalrevolutionären Szene entwickeln, in der die brillantesten Köpfe aus der Grauzone zwischen NSDAP und KPD zu Wort kamen. In der Rubrik "Vormarsch der Völker" gewährte man den antikolonialen Befreiungsbewegungen und ihren Vertretern breiten Raum, folgerichtig spielten auch vulgärgeopolitische Betrachtungen eine Rolle. Um die Jahreswende 1930/31 beteiligte Hielscher sich gemeinsam mit Jünger und Paetels Sozialrevolutionären Nationalisten an der Deutsch-Orientalischen Mittelstelle zur Förderung des antiimperialistischen Befreiungsnationalismus. Gelder beschaffte Franz Schauwecker vom Stahlhelm-nahen Frundsberg-Verlag, und neben dem altgedienten Putschisten F.W. Heinz sollte Schauwecker sich zu einem der enthusiastischsten Hielscher-Gefolgsleute entwickeln. Weitere Finanzmittel kamen vom unvermeidlichen Kapitän Ehrhardt. Die Debütausgabe des "Reiches" erschien am 1. Oktober 1930, und kein Geringerer als Ernst Jünger steuerte zur Eröffnung einen Beitrag bei.

Hielscher selbst schrieb in "Die letzten Jahre", Weimar und mit ihm die Wilhelminische Ordnung seien im Zerfall begriffen, es gehe wie seine Parteien bis hin zu NSDAP an Selbstzersetzung infolge von Unfähigkeit der Führer zugrunde. Die Weltwirtschaft kranke an der Weimarer Republik wie an einer unheilbaren Wunde. Asien blicke gärend auf Deutschland, von wo der Funke kommen sollte, der den letzten Sprengstoff entzündet: "Die Versuche des Westens, von der Wirtschaft her die kommende Gefahr zu bannen, verfangen nicht mehr. Die Mächte des Ostens tasten eine jegliche nach einem neuen Halt; aber keine hat die Lösung. Niemand weiß weiter. Und in dem deutschen Raum inmitten dieser tausendfältigen Verwirrung brodelt es unaufhörlich.

Hier ist der Ort und hier liegt die Aufgabe für die Menschen des Reiches, die durch den Weltkrieg hindurchgegangen sind; des heimlichen Reiches, das inmitten der Völker sichtbare Gestalt annehmen will. Wer dem Weltkriege seine Haltung und seine Zuversicht verdankt, weiß, daß er ein Sieg des Reiches gewesen ist, den Osten erweckend, den Westen zersetzend, den Zusammenbruch des wilhelminischen Fremdkörpers vorbereitend...

Die Wissenden erkennen sich auf den ersten Blick. Sie haben einander gefunden und finden sich weiter, seitdem die Verwandlung des Weltkrieges ihr Bewußtsein erfüllt hat. Seit dieser Zeit ist die Unruhe zur Arbeit geworden und die Suche zum Entdecken...Die Menschen des unsichtbaren Kerns haben einander entdeckt. Sie rühren keinen Finger gegen den Westen, der sich imn Staat der Weimarer Verrfassung so guit wie jenseits des Atlantischen Ozeans von selbst zerstört. Was heute Erfolg heißt, ist ihnen gleichgültig. Sie haben die große Geduld.

Denn die Entscheidung, die sich heute vorbereitet, liegt tiefer als irgend eine Entscheidung der bisherigen Geschichte. An ihr sind alle Mächte beteiligt. Der Weg zu ihr ist Bekenntnis und Staatskunst zugleich. Nur wo beides ineinanderwirkt, geschieht d a s R e i c h."

Neben dem "Reich" widmete Hielscher sich weiteren publizistischen Projekten, beispielsweise beteiligte er sich am 1931 von Goetz Otto Stoffregen herausgebenenen Sammelband "Aufstand - Querschnitt durch den revolutionären Nationalismus". Im Beitrag "Zweitausend Jahre" hieß es: "Das Kennzeichen, durch welches sich unsere Geschichte von der jedes anderen Volkstums unterscheidet, ist die wechselseitige Verschlungenheit von Innerlichkeit und Macht. Unsere Innerlichkeit enthält den Willen zur Macht; und unsere Macht enthält den Willen zur Innerlichkeit." Innerlichkeit und Machtwille wurden durch den Einbruch des Christentums getrennt. Der Weg der Innerlichkeit führt von der Ursage über Mystik, Reformation und Idealismus bis hin zu Nietzsche. Der Weg der Macht wiederum verlief von Theoderich den Großen über Heinrich VI von Hohenstaufen, Gustav Adolf und Friedrich den Großen bis zu Bismarck. Die wechselseitige Bezogenheit von Innerlichkeit und Macht hatte niemals aufgehört. Immer wieder erfolgten Anläufe, die Einheit beider Begriffe herzustellen, und unter der Macht des Reiches alle germanischen Stämme zu einen. "So ist nun in dreifachem Anlauf vor aller Augen das Ziel errichtet worden, das die Macht des Reiches zu verwirklichen bestimmt ist; und es bedarf der Waffe, mit der die Deutschen das ihnen jetzt sichtbare Ziel erreichen können. Diese Waffe heißt Preußen. Preußen ist kein Stamm, sondern eine Ordnung. Es gibt nur Wahlpreußen. Aus allen Stämmen des Reiches strömen die wagemutigsten, abenteuerlichsten, kriegerischsten Herzen zusammen; es entsteht der Staat Friedrich Wilhelms I und Friedrichs des Großen." Ziel war der Kampf gegen den westlichen Materialismus, "und gerade gegenüber diesem bereits in Deutschland eingedrungenen Gift."

"Ob Luther gegen Rom kämpft, oder ob Goethe den Beginn des Johannesevangeliums neu übersetzt: ‚Im Anfang war die Tat' - immer drängt die Innerlichkeit zum Tun; sie enthält den Willen zur Macht, die Sehnsucht, die das Amt herbeiglaubt und die Menschen zum Werke drängt.

In Nietzsche vollends wird dieser Drang zum bewußten Wollen: die Innerlichkeit erkennt ihr Getriebenwerden als Willen zur Macht." Nietzsche forderte den "ins Geistige gesteigerten Fridericianismus", bindet dieses neue Menschentum an Gestalten wie Friedrich II von Hohenstaufen und Friedrich II. den Großen. Auf Nietzsche und Bismarck folgte der Weltkrieg, der "trotz der scheinbaren Niederlage den größten Sieg bedeutet, den Deutschland jemals errungen hat". "Zum ersten Mal, seit die Erde steht, gibt es keine voneinander abgetrennten Kampffelder mehr, so wie es z.B. den ostasiatischen, den vorderasiatischen oder den Kulturkreis des Mittelmeeres gegeben hat, sondern die Erde ist ein einziges Schlachtfeld geworden, ein Chaos, in welchem alle Kräfte zugleich um den Sieg streiten, ein Chaos, das alle Kräfte durch diesen Streit verwandelt und von Grund auf umschöpft."

Im gleichen Jahr legte Friedrich Hielscher sein mit Hilfe des Frundsberg-Verlages herausgebenes Grundlagenwerk "Das Reich" nach. Ein Volk entsteht Hielscher zufolge aus der Gemeinschaft von Schicksal und Bekenntnis. Das Blut erhält seinen Rang durch eine Entscheidung und nicht durch die Biologie. Deutschtum/Deutschheit leiten sich nicht durch Abstammung und staatliche Definition, ab, sondern aus Gesinnung und Glauben. Der Reichsbegriff wird vom politischen zum religiös-metaphysischen, in der Geschichte wirkenden Prinzip einer föderativen Ordnung Europas - unter Führung des preußischen Geistes. Die Nationalstaaten sollten sich in Stämme und Landschaften auflösen, und aus diesen verkleinerten Einheiten war etwas Größeres zu schaffen, das über die Nationalstaaten hinausging.

Im gleichen Jahr legte Friedrich Hielscher sein mit Hilfe des Frundsberg-Verlages herausgebenes Grundlagenwerk "Das Reich" nach. Ein Volk entsteht Hielscher zufolge aus der Gemeinschaft von Schicksal und Bekenntnis. Das Blut erhält seinen Rang durch eine Entscheidung und nicht durch die Biologie. Deutschtum/Deutschheit leiten sich nicht durch Abstammung und staatliche Definition, ab, sondern aus Gesinnung und Glauben. Der Reichsbegriff wird vom politischen zum religiös-metaphysischen, in der Geschichte wirkenden Prinzip einer föderativen Ordnung Europas - unter Führung des preußischen Geistes. Die Nationalstaaten sollten sich in Stämme und Landschaften auflösen, und aus diesen verkleinerten Einheiten war etwas Größeres zu schaffen, das über die Nationalstaaten hinausging.

Ergänzend heißt es in "50 Jahre unter Deutschen": "In Wahrheit muß...im Innern des Menschen angefangen werden, im eigenen zuerst und dann im Bunde mit denen, die des gleichen Willens sind. Aber das ist mit keiner noch so reinen Sittlichkeit zu schaffen, schon gar mit keiner Moral und vollends nicht mit Anordnungen und Vorschrift." Sondern nur der Glaube "gibt uns das Gesetz als das Gebot der Götter"

"Das Reich": "Die schöpferische Kraft kann nicht auf dem einen Gebiet wirken und auf dem anderen nicht. Sie kann nicht vor dem Alltag halt machen oder vor den Umständen oder der Not. Sie erfüllt den ganzen Menschen. Er mag anpacken, was er will, er mag versuchen, sich in nichtige Dinge zu flüchten: Die schöpferische Kraft folgt ihm, sie treibt ihn weiter, und am Ende erkennt er, daß alles, was er angefaßt hat und was ihm begegnet ist, notwendig und gut gewesen ist um seines Werkes willen, für das er lebt, für das er gelebt wird, das durch ihn hindurch wirkt. Darum bilden alle Menschen, hinter denen ein und dasselbe Wesen steht, nicht auf irgendwelchen einzelnen Gebieten, sondern ihr ganzes Leben hindurch, in jeder Hinsicht unabdingbar eine Einheit des Wirkens. Es müssen ein und dieselben Ereignisse sein, die sie fördern oder hemmen: ein und dieselben Begegnungen müssen für sie Tiefe oder Licht bedeuten: sie haben dasselbe Schicksal, das heißt aber: sie sind ein Volk. Kein Ding in Raum und Zeit bindet endgültig: nicht die Abstammung, nicht die Sprache, nicht die Umgebung. Dem alleine steht der einzelne frei gegenüber. Allein seine schöpferische Kraft, die seinen Willen überhaupt erst bildet, aus dem sein Wille in jedem Augenblick gebildet wird, bindet ihn notwendig, sie ist der Kern seines Wesens. Damit unterscheidet sich ein Volk von einem bloßen Abstammungsverband und von jeder Verbindung, die nur durch äußere Umstände zusammengehalten wird...Nur die seelische Besessenheit durch dieselbe schöpferische Kraft gestaltet aus einer Vielheit vertretbarer Menschen ein Volk, indem ein und dieselbe Wirklichkeit durch die Tat bezeugt wird. Das Volk ist Einheit des Bekenntnisses und des Schicksals. (...) Geduld ist die oberste Tugend dessen, der verwandeln will. Wer keine Geduld hat, erreicht nichts.

Die Entscheidung, die sich hier vorbereitet, bedeutet die vollkommene Vernichtung der heutigen Ordnungen und Güter; und es ist an der Zeit, mit jenen hoffnungslosen Gedanken aufzuräumen, die noch retten wollen, was zu retten ist. Es ist nichts mehr zu retten. Alle äußeren Gestaltungen der Gegenwart brauchen und unterstützen die westliche Verfassung des öffentlichen und des Einzellebens. Sie setzen die Heiligkeit des uneingeschränkten Eigentums voraus, den Verdienst als treibenden Anreiz des Handelns und die Wohlfahrt aller als Ziel der Gemeinschaften. Hier darf nichts gerettet werden. Die inneren Güter aber, die nicht des Westens, sondern des Reiches sind, sind unzerstörbar. Wer sie für gefährdet hält, kommt für die deutsche Zukunft nicht in Frage. Denn er glaubt nicht an sie. Wer glaubt, zweifelt nicht.

Die Vernichtung dessen, was heute besteht, ist sogar notwendig. Denn daß der Westen die Entscheidung gerade in dem Raume zwischen Rhein und Weichsel sucht, liegt an dem Rang, den dieses Gebiet innerhalb der - westlichen - Weltwirtschaft besitzt. Weil China, Indien und Rußland bereits zum größten Teile aus ihr heraus gefallen sind, darf sie Deutschland nicht auch noch verlieren, um keinen Preis. Sonst ist sie selbst verloren. Darum setzt der Untergang des Westens die Vernichtung dessenh voraus, was heute Deutschland heißt, was mit dem Wesen des Reiches nur mehr den Namen gemeinsam hat.

Die Ereignisse des Dreißigjährigen Krieges werden gering vor dieser Zukunft. Er hat die Erde noch nicht aufgerufen. Aber der Erste Weltkrieg hat es getan; und dadurch wird die Wucht der nächsten Jahre, der nächsten Jahrzehnte, der nächsten Jahrhunderte größer, als die der fünftausend Jahre bewußter Erdgeschichte, auf die wir zurückblicken können. Wer von dem Werke, das ihm obliegt, die Erhaöltung und Bewahrung überkommender Dinge erwartet, zeigt nur, daß er die Größe der Verwandlung nicht erkannt hat, in der die Völker seit 1914 leben.

Es gibt heute keine sichtbaren Werte des Reiches. Es lebt inwendig in den Herzen; oder es würde nicht leben.Zerschlagen muß das Eigentum werden, das dem Westen gehört, das den westlichen Menschen gehört. Der Westen würde längst besiegt sein, wenn er nicht die Geister der Menschen gefangen hätte, wenn nicht wirklich jeder, der um seines Vorteiles willen lebt, damit zum Werkzeuge, zum Untertan und Helfer des Westens würde. Zerschlagen muß die ständische Haltung werden, weil die hierarchische Befriedung der Stände, die - gutgläubig oder nicht gutgläubig - vom Süden her verkündet wird, nur der pax Romana, der friedevollen Herrschaft Roms sich einfügt, welche die Völker dem Heiligen Stuhle unterwirft, und weil die Ziele Roms mit denen des Westens gemeinsam auf die Erhaltung des Staates der Weimarer Verfassung gerichtet sind. Zerschlagen muß die Möglichkeit der kolonialen Ausdehnung werden, weil der Herrschaftsanspruch des Reiches nichts mit dem kolonialen Märktekampf zu tun hat, weil, nicht nur der Begriff der ‚Kolonie', sondern auch jedes koloniale Streben dem Willen zur prosperity und nicht dem Willen zur Macht dient.

Man darf gewiß sein, daß die allernächsten Jahre diese Vernichtung vorbereiten und fördern werden. Jener Gleichlauf der Selbstzersetzung des Westens und des Aufbaus der Reichszellen, jene langsame und zögernde Annäherung zweier Bahnen, die sich erst im Augenblick der Entscheidung überschneiden, deren Überschneidung der entscheidende Augenblick ist, prägt sich bereits heute - und von Tag zu Tag mehr - in der Verelendung des Volkes aus. Es wird nicht fünf Millionen, sondern fünfundzwanzig Millionen Arbeitslose geben. Es wird nicht mehr Haß und Hoffnung geben, sondern nur noch Verzweiflung und Zuversicht.

Diese Zuversicht, welche die kommende Vernichtung bejaht, glaubt an das unvernichtbare ewige Wesen des Reiches. Sie weiß, daß im Wandel der sichtbaren Geschichte immer nur die unsichtbare Wirklichkeit lebt. Sie weiß, daß eine jede Kraft des Ewigen selber unwandelbar und ewig ist, und daß kein Werk, kein schöpferisches Tun um des zeitlichen Seins willen geschieht, sondern immer und nur um der Macht des Reiches willen, welches sein zeitliches Reden und Schweigen, Tun und Stillesein, sichtbares oder verborgenes Bildnis heraufführt, wie es ihm beliebt. Das kriegerische Herz verwechselt die zeitliche Erhaltung nicht mit der göttlichen Unsterblichkeit. Es ist unsterblich und freut sich der zeitlichen Vernichtung als der Bürgschaft seiner unüberwindlichen Gewalt. Der Untergang, dem sich die Deutschen, und das heißt immer und immer wieder: die Menschen des Reiches, heute aussetzen, führt die Freiheit herauf, um die seit der ersten Schlacht des Ersten Weltkrieges gekämpft wird, die Freiheit, welcher als erwünschtes Werkzeug der Westen selber dient, dessen Griff über die Erde das Zeitalter der großen Kriege des Reiches ermöglicht."

5. Unterirdisch im Dritten Reich

Die Nationalisten alten Schlages und die KPD konnten hier begreiflicherweise nicht folgen. Ernst Niekisch urteilte: "Das ist ja nicht mehr Nationalismus". Alfred Kantorowicz erkannte in der Vossischen Zeitung am 14. September 1931 als einer der wenigen, wohin die Reise ging: Das sei weder Politik noch Philosophie, sondern Theologie. Otto-Ernst Schüddekopf bemerkt sehr treffend, die Disproportion zwischen dem engen deutschen Nationalismus des 19. Jahrhunderts und den heraufnahenden globalen Machtkämpfen suchte man im radikalen Nationalismus Weimars zu überwinden. Der Sprung in die Freiheit durch die Idee des "Reiches" der Deutschheit, die mit den Voraussetzungen des deutschen Nationalstaates nichts mehr zu tun hat - der Nationalsozialismus bedeutete demgegenüber einfach Reaktion. Kollektivistisches Denken und bolschewistische Lebensform wurden als typenbildende Kraft akzeptiert. So konnte man die alten Massenparteien aus den Angeln heben und sich selbst als die die Zukunft des Reiches bestimmende Kraft definieren.

Nach der NS-Machtergreifung stellte Friedrich Hielscher die Herausgabe des "Reiches" ein, um sich der unterirdischen Arbeit gegen den Hitlerismus zu widmen. Ziemlich zutreffend rechnete er mit einer Dauer des Tausendjährigen Reiches von ca. 12 Jahren, während der Großteil der nationalrevolutionären Parteigänger Hitler zu diesem Zeitpunkt nicht ernst nahm. Während Persönlichkeiten wie Schauwecker sich der neuen Ordnung anpaßten, blieben Friedrich Hielscher, die Gebrüder Jünger und Ernst Niekisch als intellektuelle Kristallisationspunkte des nationalrevolutionären Untergrundes. Der Hielscher-Zirkel entwickelte sich zu einer kleinen Untergrundzelle, zu der auch der ehemalige Ehrhardt-Adjutant Franz Liedig gehörte. Über Liedig und August Winnig hielt die Gruppe lockeren Kontakt zu oppositionellen Militärs. Verbindungen bestanden zur sozialdemokratischen Gruppe um Mierendorff, Leuschner, Haubach und Reichwein.

Von größerer spiritueller Bedeutung war die 1933 nach dem Umzug nach Potsdam erfolgte Gründung der Unabhängigen Freikirche UFK als heidnisch-pantheistischer Glaubensbewegung auf indogermanischer Grundlage: "Ich glaube an Gott den Alleinwirklichen. Ich glaube an die ewigen Götter. Ich glaube an das Reich." Heidnische Elemente aus der deutschen Klassik und Romantik wurden mit dem ketzerischen Pantheismus eines Johannes Scotus Eriugenas, Nietzsche und dem überlieferten keltisch-germanischen Volksglauben verknüpft zu einer sehr bald für Außenstehende äußerst schwer zu erfassenden theologischen Einheit. Die Theologie der UFK war kein statisches Gebilde, sondern wie das Reich eine dynamisch weiterzuentwickelnde Aufgabe.

1934 beteiligte Hielscher sich am von Curt Horzel herausgegebenen Sammelband "Deutscher Aufstand" und veröffentlichte wahrhaft prophetische Sätze: "Erster Satz: Der wilhelminische Staat hat den Krieg verloren, aber Deutschland hat ihn gewonnen.

Zweiter Satz: Deutschland hat den Krieg nicht nur dadurch gewonnen, daß es neue innere Kraftquellen erschlossen hat, sondern auch durch die Erschütterung der ganzen Erde, durch die alle Voraussetzungen aller Völker ins Wanken geraten sind.

Dritter Satz: durch die von Deutschland ausgehende Erschütterung ist es zum entscheidenden Lande auch des vor uns stehendem Zweiten Erdkrieges geworden." Diesen hatten schon Nietzsche, Trotzki und Ludendorff prophezeit. "Es leuchtet ein, daß dort, wo alle Kräfte sich überschneiden, die Entscheidung fallen muß." Der Kampf zwischen Imperialismus und Revolution wird hier ausgefochten, zwischen Bolschewismus und Hochkapitalismus, zwischen Asien und West. Deutschland als Land der Mitte sucht nach einer Synthese zwischen den Gegensätzen. Als Ausweg forderte Hielscher den Kontinentalblock Deutschland-Sowjetunion-China.

Eine beinahe antik anmutende Tragödie nahm ihren Anfang, als Hielschers Freund und Schüler Wolfram Sievers 1935 zum Geschäftsführer der SS-nahen Kulturstiftung Ahnenerbe avancierte. Die völkisch-indogermanischen Elitevorstellungen der Hielscher-Gruppe trafen sich durchaus mit denjenigen der SS. Hatte Hielscher sich in den Elfenbeinturm zurückgezogen, so versuchte der aktivistische Praktiker Sievers nun, das Konzept in die Tat umzusetzen und geriet außer Kontrolle. Zunächst beteiligte der Geschäftsführer sich daran, das bäuerlich-defensive Element des Reichsnährstandes aus dem Ahnenerbe hinauszudrängen und stattdessen dem soldatischen Charakter der SS-Ideologie mehr Platz zu verschaffen. Von Bedeutung war neben frühgeschichtlichen, volkskundlichen und indogermanologischen Forschungen z.B. der Versuch, die deutschen Hochschulen zwecks Schaffung eines neuen wissenschaftlichen Geistes von der Schutzstaffel infiltrieren zu lassen. Im Januar 1941 legte Sievers in einem internen Memorandum die Ziele der Erforschung von Raum, Geist und Tat des nordischen Indogermanentums dar: "Hauptziel ist es, vom Kulturellen her in Deutschland selbst das Reichsbewußtsein neu zu wecken, bezw. zu vertiefen, von dessen einstiger Größe beispielsweise ein Straßburger Münster, die Prager Burg, das Fuggerhaus auf dem Warschauer Altmarkt, die flandrischen Tuchhallen noch heute Zeugnis ablegen über Jahrhunderte hinweg, in denen das Reich schwach und im böhmisch-mährischen Raum, in den Niederlanden, im Flamentum, in der Schweiz das Gefühl der Zugehörigkeit zum Reich verloren gegangen war. Es wird notwendig sein, die Verbindungen bloß zu legen, die dennoch niemals abgerissen sind, die Überfremdung durch Kirche, Liberalismus, Freimaurerei und Judentum hinwegzuräumen und die Wiedervereinigung der Menschen germanischen Blutes im Reich zu erleichtern, das - lange seiner selbst durch internationale Ideologien entfremdet - trotz allem germanische Art am stärksten gewahrt hat."